【Lawrence J. Lau】The Impacts of the Trade War and the COVID-19 Epidemic on China-U.S. Economic Relations

The China-U.S. trade war, which began in mid-2018 and is still ongoing despite an interim “Phase 1” truce, and the COVID-19 epidemic, have not only reduced Chinese growth rates (down to 6.1% for 2019 and 1.8% for the first half of 2020), but also led to the deterioration of China-U.S. relations to arguably the lowest point since 1971. The trade war lowered the Chinese rate of growth from 6.7% in 2018 to 6.1% in 2019, but the COVID-19 epidemic has lowered the rate further to a projected 3.4% in 2020. The trade war per se caused only a very slight decline in the rate of growth of the U.S. economy in 2019 but the COVID-19 epidemic has resulted in a projected contraction of the U.S. economy in 2020 of more than 5%.

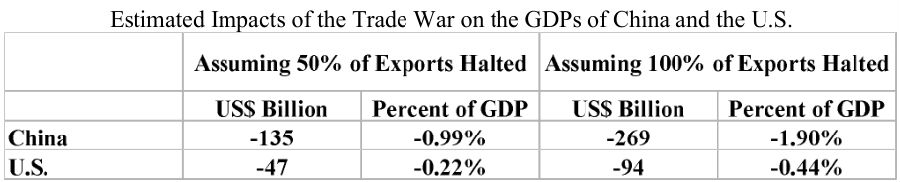

The mutual imposition of tariffs by both the United States and China on each other’s imports, implemented in 2019, definitely had adverse impacts on both economies. In 2019, the ratio of Chinese exports of goods to the U.S. to Chinese GDP was 3.0%, compared to the ratio of U.S. exports of goods to China to U.S. GDP of 0.5%. Thus, the impacts of the tariffs were expected to be larger on the Chinese economy. However, the total (direct and indirect) domestic value-added content of U.S. exports was 89% compared to the 66% of Chinese exports. On the assumption that half of the Chinese exports to the U.S. was halted, it would imply a total loss of Chinese GDP of almost 1%, or approximately US$135 billion (in 2019 prices, similarly for all other US$ values). On the assumption that half of U.S. exports of goods to China was halted, it would amount to a loss of U.S. GDP of 0.22%, or approximately US$47 billion, which is not that significant for the U.S. economy. If all Chinese exports to the U.S. cease, the maximum damage to the Chinese economy may be estimated to be approximately 1.9% of Chinese GDP. If all U.S. exports of goods to China cease, the loss of U.S. GDP may be estimated to be approximately 0.44%. Thus, in both absolute and relative terms, the potential costs of the trade war are higher for China than for the U.S.

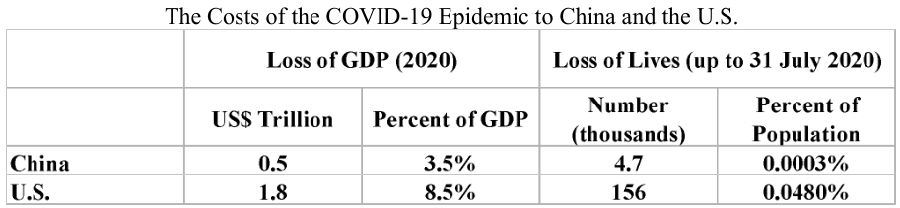

As of 31 July 2020, the U.S. had more than 4.7 million cumulative COVID-19 confirmed cases and 156 thousand cumulative deaths, the highest such numbers of any country in the world, compared to less than 85,000 cumulative cases and less than 4,650 cumulative deaths for the Mainland of China, which has four times the population of the U.S. On 31 July 2020, the U.S. population infection and population mortality rates were 14,301 and 476 per million persons respectively, compared to China’s 60.2 and 3.3. The total loss of Chinese GDP due to the COVID-19 epidemic in 2020 may be estimated as US$0.5 trillion, or 3.5% of the 2019 Chinese GDP of US$14.2 trillion. The total loss of U.S. GDP due to the epidemic may be estimated as US$1.8 trillion, or 8.5% of the 2019 U.S. GDP of US$21.4 trillion. The costs of the COVID-19 epidemic in terms of human lives are much lower in China than in the U.S. in both absolute and relative terms. The losses in terms of foregone GDP are also lower for China than for the U.S. in both absolute numbers and percentages.

The China-U.S. trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic have also brought to the forefront the possibility and desirability of a “de-coupling” of the two economies. Any major country will want to avoid being overly dependent on another country for the supply of a critical raw material, component, part or technology because of the potential disruption of the economy that an interruption of such supply may cause. Economic de-coupling per se can be costly, but may also bring benefits. The availability of an alternate second source can prevent monopolisation, reduce monopoly power, and lead to a more stable and more competitive world economy for the benefit of all consumers.

In this paper, we address specifically the de-coupling of the capital markets and higher education between China and the U.S. First, we consider capital markets. Back in 2014, the distribution of Chinese Initial Public Offering (IPO) funding broke down to approximately 43% U.S., 29% Hong Kong and 28% A-shares in Shanghai. In 2019, the corresponding percentages were 7%, 12% and 81%. The Chinese domestic capital market has already become the most important funding source for Chinese enterprises. The total market capitalisation of publicly listed Chinese enterprises was distributed 8.7% U.S., 20.9% Hong Kong and 70.4% China in 2019. The importance of New York as a source of equity capital to Chinese enterprises has greatly diminished. De-coupling of the capital markets will not have a large impact on the Chinese economy.

Second, we consider higher education. There are currently approximately 360,000 Chinese students enrolled in various institutions of higher learning in the U.S. Their annual expenditures may be conservatively estimated to be US$18 billion. Moreover, the leading U.S. universities have had first choices on the best eighteen-year-olds from China. A de-coupling will put an end to the educational exchange. Another potential problem for the U.S. is the shortage of qualified graduate students. At the present time, graduate students in science and engineering at the top U.S. research universities are drawn from three main sources—China, India and Russia. Not admitting Chinese graduate students will reduce both the quality and the quantity of graduate enrollment in these fields significantly. The de-coupling of higher education may marginally have some adverse impact on Chinese graduate students as they will lose access to the more systematic U.S. model of research training.

We present both short- and long-term projections of the Chinese and U.S. economies. We project that the Chinese economy will grow 3.4% in 2020 as a whole and 8% in 2021. We project that the U.S. economy will contract by 5.7% in 2020 but will recover quickly to grow 4% in 2021. Our long-term projections suggest that the Chinese real GDP (US$27.70 trillion) is likely to just barely edge out the U.S. GDP (US$27.69 trillion) in 2030. However, the projected then U.S. GDP per capita of US$80,400 will still be more than four times the projected then Chinese GDP per capita of US$19,000. Chinese real GDP per capita will lag behind that of the U.S. until at least the end of the 21st Century.

China-U.S. relations chilled further with the recent closure of the Chinese Consulate-General in Houston, ordered by the U.S., and the subsequent closure of the U.S. Consulate-General in Chengdu by China in retaliation. The economic, technological and geo-political competition between China and the U.S., whether friendly or unfriendly, can be assumed to be an ongoing and long-term one. It is the “new normal” for the next decade or two. The trade dispute and the dispute on the origin of the COVID-19 virus are only manifestations of the underlying potential competition between the two countries for dominance in the world.

Will the competition between China and the U.S. lead to a war? China has no intention of proselytising its ideology or system of government to other countries, least of all the U.S. Hence the China-U.S. competition is essentially non-existential, unlike the rivalry between the former Soviet Union and the U.S., which was existential. If even the former Soviet Union and the U.S. could avoid going to war in the last century, there is no reason why China and the U.S. cannot avoid a war between them. However, the relations between the two countries must be carefully managed going forward.

Download the full report:The Impacts of the Trade War and the COVID-19 Epidemic on China-U.S. Economic Relations