Eric Maskin: How to let all people benefit from globalization?

Eric Maskin is a professor at Harvard University.

In 2007, he shared the Nobel Prize in economics with Leonid Hurwicz and Roger Myerson “for having laid the foundations of mechanism design theory”.

He will attend the China Development Forum 2017 from March 18 to 20, 2017.

Editor’s note: Income inequality has brought about a series of political and economic consequences that cannot be neglected. Has economic globalization exacerbated inequality? How should we advance economic globalization in the direction of shared benefits? Over the past 20 years, globalization has extended from cross-border trade to cross-border production and trade represented by multinational companies. Based on observations of Mexico’s development after it signed the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade (GATT) in the 1980s, Professor Maskin found that the white-collar salary in Mexico was on the rise while the blue-collar income decreased, widening the income gap. This is the same case with many countries of Latin America and Asia. Hence, he concluded that globalization had not reduced inequality.

This article introduces the main opinions of Professor Maskin about economic globalization and increased inequality.

I. Globalization and inequality

In a paper (Why Haven’t Global Markets Reduced Inequality?), Maskin points out a flaw in the theory of comparative advantage and discusses the inequality in developing countries from the perspective of the influence of globalization on production. Though the theory of comparative advantage explains why free trade has narrowed the wealth gap between countries over the past 200 years, income inequality has increased in some countries with the increase of global production and economic progress of developing countries during the latest round of globalization over the past 20 years. He then gives explanations about the phenomenon.

Different from the model of comparative advantage, workers work with each other across countries in Maskin’s model. Economic globalization is not only reflected in the growth of international trade but also the building of global industrial chain. Take Apple Inc. for example. While its products are designed in California, the parts are manufactured in different regions of the world and assembled in China.

Maskin supposes workers cooperate through skills match. An individual with a higher skill level (such as a professional manager or researcher) will generate more output when he matches with a senior technician compared to with an ordinary technician. Hence, workers can get higher income through matching with those with higher skills.

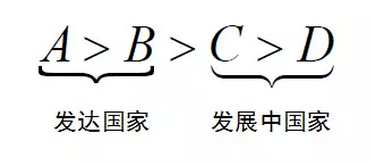

Suppose there are two countries in the model, one developed and the other developing. The developed country has workers of two skill levels, A and B. The developing country also has workers of two skill, levels C and D. Moreover, A>B>C>D.

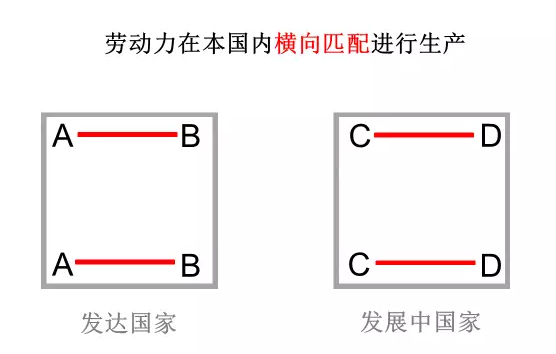

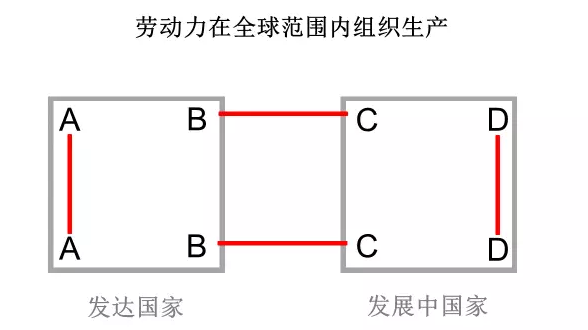

Before the industrial chain is globalized, workers only cooperate within the home country. In this case, domestic “cross matching” generates the greatest output, and market competition will drive workers to opt for “cross matching”. After globalization, changes will take place in the labor force market. Companies organize production on a global scale and the international industrial chain takes shape, giving rise to a new matching structure. Matching on a global scale generates more output than that on a national scale, and this is one benefit brought by globalization.

In the latter case, workers with D-level skills lose the opportunity to work with C-level ones, but can’t work with A-level ones since the skill gap is too large. Hence, D-level workers have to work with those with the same level of skill, and wealth gaps will widen in developing countries. As to the phenomenon, Professor Maskin suggests that “the right thing to do is not to try to stop globalization” and the best way to reduce inequality is through training and education to raise workers’ productivity. He thinks that the third parties (governments, international agencies, foreign aid, etc.) should pay for skill training, so that low-skilled workers can also get engaged in globalized production and benefit from globalization.

II. Maskin and China

Professor Maskin has visited China many times and follows China’s reform and development. In March 2016, he attended the China Development Forum and co-authored with Bai Chong’en the background report titled Evaluat

I. Globalization and inequality

In a paper (Why Haven’t Global Markets Reduced Inequality?), Maskin points out a flaw in the theory of comparative advantage and discusses the inequality in developing countries from the perspective of the influence of globalization on production. Though the theory of comparative advantage explains why free trade has narrowed the wealth gap between countries over the past 200 years, income inequality has increased in some countries with the increase of global production and economic progress of developing countries during the latest round of globalization over the past 20 years. He then gives explanations about the phenomenon.

Different from the model of comparative advantage, workers work with each other across countries in Maskin’s model. Economic globalization is not only reflected in the growth of international trade but also the building of global industrial chain. Take Apple Inc. for example. While its products are designed in California, the parts are manufactured in different regions of the world and assembled in China.

Maskin supposes workers cooperate through skills match. An individual with a higher skill level (such as a professional manager or researcher) will generate more output when he matches with a senior technician compared to with an ordinary technician. Hence, workers can get higher income through matching with those with higher skills.

Suppose there are two countries in the model, one developed and the other developing. The developed country has workers of two skill levels, A and B. The developing country also has workers of two skill, levels C and D. Moreover, A>B>C>D.

Before the industrial chain is globalized, workers only cooperate within the home country. In this case, domestic “cross matching” generates the greatest output, and market competition will drive workers to opt for “cross matching”. After globalization, changes will take place in the labor force market. Companies organize production on a global scale and the international industrial chain takes shape, giving rise to a new matching structure. Matching on a global scale generates more output than that on a national scale, and this is one benefit brought by globalization.

In the latter case, workers with D-level skills lose the opportunity to work with C-level ones, but can’t work with A-level ones since the skill gap is too large. Hence, D-level workers have to work with those with the same level of skill, and wealth gaps will widen in developing countries. As to the phenomenon, Professor Maskin suggests that “the right thing to do is not to try to stop globalization” and the best way to reduce inequality is through training and education to raise workers’ productivity. He thinks that the third parties (governments, international agencies, foreign aid, etc.) should pay for skill training, so that low-skilled workers can also get engaged in globalized production and benefit from globalization.

II. Maskin and China

Professor Maskin has visited China many times and follows China’s reform and development. In March 2016, he attended the China Development Forum and co-authored with Bai Chong’en the background report titled Evaluation on Local Officials of China. He pointed out at the Forum that wealth gaps and increased inequality are the key issues that need to be addressed by China. “The solution to reduce inequality is not to make the rich poorer but to enrich the poor. So the best way is, through education and training, to improve the poor’s capacity to get a decent income.” He is scheduled to attend this year’s Forum.